Through the looking glass

Research news

We think of Australia as “the land of the fair go” - but is Australia really egalitarian?

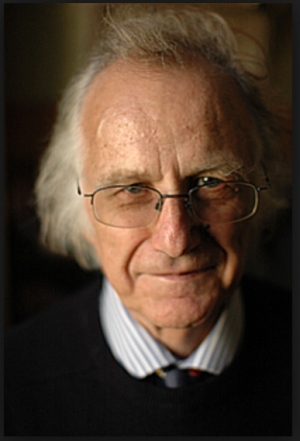

Our national sense of self and the mythology that we have built around being “Australian” goes back to the convict days. But Australians should look more closely at these assumptions, advises internationally acclaimed anthropologist, Professor Bruce Kapferer, who is about to complete a four-month Thinker-in-Residence visit at Deakin.

Professor Kapferer has spent many years researching the role of mythologies in shaping national identity.

“There is a central myth that we are an egalitarian nation, but how egalitarian are we? The way the egalitarian debate is presented paradoxically helps to hide how unegalitarian we are,” he says.

“In one way there is an emphasis on how the individual develops, but there are certain forms of privilege that cut people out, for instance, through the public versus private education system. In this respect, Australia lies between the Westminster system on one side and Washington on the other, where the emphasis on individual success seems to contradict social responsibility.”

Challenging the very foundations of how society works has been a key motivator for Professor Kapferer, whose perspective epitomises the notion of the “critical academic”, where all assumptions should be questioned and challenged.

Professor Kapferer has travelled the world in his quest to understand humanity from all angles. He has spent years in hot spots such as Zambia in Africa and with the Tamils in Sri Lanka, taking Marxist and post-structuralist perspectives to his research in anthropology - the discipline known as the bridge between the humanities and sciences.

Taking leave from his post as Professor of Anthropology at the University of Bergen, Norway, Professor Kapferer has been collaborating with staff and students within the Alfred Deakin Research Institute on refugee policy. While his research career has spanned many areas, over recent years he has specialised in social and political processes among communities in South Asia, Southern Africa and Australia.

Professor Kapferer was awarded the prestigious Huxley Medal, the highest honour of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, in 2011.

While an Australian - he founded the Anthropology Department at the University of Adelaide in the 1960s - he has spent much of his career overseas and says he has noticed many changes since he last spent time here, notably the shift in the structure of the state, which has become “much more corporatised”. “Australia is one of the most deregulated countries in the world now,” he says.

During his visit, he has taken a strong interest in announcements relating to manufacturing, such as the recent Toyota, SPC and Alcoa announcements.

“There is currently a huge social reconfiguring going on,” he says. “We are seeing the end of Toyotism - the dominant management and labour process of most developed capitalist countries at the end of the 20th century.”

Toyotism is defined as the division of the workforce into a privileged, full-time relatively secure core of skilled workers on one hand, and a mass of part-time casual, often female or immigrant, labourers on the other.

Professor Kapferer is concerned that greater unemployment could lead to more problems of control and potential for violence.

“There is potential for further breaking up of rural communities and an increase in city enclaves of disadvantage,” he says.

He is also concerned about the racial prejudice he has observed here, particularly in relation to boat people. “Refugees are not just economic immigrants. Their lack of wealth cannot be separated from the fact that many of them have suffered hellish conditions. The situation faced by the Tamils is horrific,” he says.

He ties the increase in prejudice to the effects of globalisation and “the last vestiges of industrial production. “People are worried about their livelihoods,” he says. “It is not rational.”

Instead, he argues that refugee policy should be viewed from a different angle. “Refugees could actually help us,” he says. “For instance, the Tamils live in dry and arid zones in Sri Lanka. With climate change affecting farming in Australia, their experience in dry land agriculture could provide Australian farmers with new agricultural techniques that would be very valuable.”

Bruce Kapferer’s interest in the world makes it unlikely that he will ever retire quietly. He says that he would love to do a smaller study of Tasmania as one of his next projects, as it offers “a microcosm of what’s happening across Australia, in areas such as its treatment of Aborigines, convicts, employment, the environment etc.”

Professor Kapferer believes that criticism is essential to a healthy democracy, and, in this respect, Australia has a good track record.

“Australia has always had a critical population,” he says. “While there has been an expansion of control over media and information - and a whittling of criticism and general debate - people are still feeding debate everywhere, particularly on the internet.”

Share this story

Professor Bruce Kapferer

Professor Bruce Kapferer