End of a Colossus

Research news

By Dr Jonathan Ritchie

Why, man, he doth bestride the narrow world?

Like a Colossus; and we petty men?

Walk under his huge legs …

(Cassius to Brutus, Julius Caesar, Act I, Scene II)

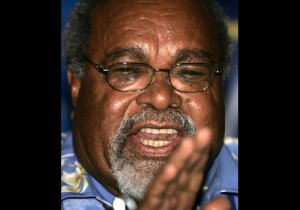

Papua New Guinea’s own Colossus, Grand Chief Sir Michael Somare, has retired from politics, due to ill health.

No other person, on either side of the Coral Sea, has so dominated the shared history of Papua New Guinea and Australia as Sir Michael has since he began in public life in the middle of the 1960s. He was PNG’s first, and until yesterday, last Prime Minister; a player in the rough and tumble – on occasions, literally – of the country’s political life; and the most known and recognizable face of Papua New Guinea. As said of Caesar in the lines from Shakespeare quoted here, Somare did indeed ‘bestride the narrow world’ of his country and the region, and all others, in some way, have walked ‘under his huge legs’.

Like Caesar, Somare has been down before, and unlike Caesar, he has not been assassinated. He has come up again, ready to fight, on numerous occasions: perhaps most notably when he became Prime Minister for the fourth time following the 2002 election. However, while (to quote another moderately well-known writer, Mark Twain) the ‘reports of his death have been greatly exaggerated’, there is little chance that the seventy-five year old Somare will again rise to the contest.

Michael Tom Somare was born in Rabaul in 1936, the son of Ludwig Somare Sana and Kombe Somare. He was educated, initially by the occupying Japanese, and following the ending of the Pacific War, in the Australian Administration’s system of schools that began to grow with the increased focus on education under both Labor and coalition Governments. In 1956, Somare (called Michael Tom at this stage) trained as a teacher at the Sogeri Education Centre and taught for the next five years at various schools around the Territory of Papua and New Guinea. With other young Papua New Guineans considered to have potential, he returned to Sogeri in 1962 to complete his secondary education. Some time as a radio announcer followed, before he came to Port Moresby to undertake further studies at the Administrative College in 1965.

The decision in late 1964 to pay indigenous public servants a small fraction of the rate received by Australians at the same level helped to make Somare a radical, as it did for other young and educated Papua New Guineans. At the Administrative College he helped form the famous ‘Bully Beef Club’, an informal political discussion group that met around the eponymous food staple for the students, and in early 1967, with other members (the ‘thirteen angry young men’) he signed a submission that has passed into history as an early demand for home rule. In June of the same year the Pangu Pati was formed by Somare and his group, and in the 1968 elections thirteen candidates associated with Pangu were successful in gaining seats in the House of Assembly. In the House, they formally identified themselves as Pangu members and under Somare’s leadership they worked as an Opposition to the Australian administration.

In April 1972 Somare led Pangu into a coalition with other parties that was the historic first Papua New Guinean government, albeit of what was still an Australian territory. He became Chief Minister, from which position he took the country into independence on 16 September 1975, as the new nation’s founding Prime Minister, at the age of only thirty-nine.

He remained as Prime Minister (winning the next election, in 1977) until he was unseated in a no-confidence motion in March 1980, his demise coming at the hands of his erstwhile coalition colleague and deputy, Julius Chan. Chan’s Government being no more successful than the one it replaced, a Pangu-led coalition returned to power in 1982, and Somare commenced his third term as Prime Minister, until he was again ousted in another no-confidence motion, this time replaced by the Western Highlander, Paias Wingti. Thirteen years after becoming the head of the first indigenous Government, and ten years after taking PNG into independence as its first Prime Minister, surely Somare could have been allowed to step away from political life; but he maintained a senior role over the following seventeen years, as Foreign Minister in the Government led by Sir Rabbie Namaliu from 1988 to 1992 and again under Sir Bill Skate in 1999. In 2002, he again became Prime Minister, for the fourth time, and in 2007, he was re-elected, making him by far the longest-serving elected political leader in the Pacific region.

From the 1980s (when a long-running Inquiry into the Forest Industry implicated him in corrupt dealings) Somare’s reputation has been tarnished, to the extent that in late 2010 he stepped down temporarily while an investigation was under way into his financial affairs. He never returned to the Prime Ministership (although he retained the office, his deputy, Sam Abal, has acted in the role since Somare stepped aside). An old man of seventy-four by this time, Somare took the chance to undergo surgery on his heart and with subsequent complications, his health has not improved sufficiently for him to return to the Prime Ministership and so he has, at last, retired.

Beyond the obvious observation that, as one who was there at the beginning, remained through the middle, and has only just left the arena, he has been our very own Colossus, it is still too early for a full assessment of Somare’s place in the history of PNG, the region, and the decolonised world. There are, however, three more-or-less uncontroversial conclusions that can be made about his importance for many, if not all, Papua New Guineans.

The first is that there should be a great debt that is owed to him and others like him who worked to help create a modern, vibrant, and – in the main – unified nation from what had been only a few years before independence a divided and dependent collection of tiny communities. It is sometimes hard to recall the enormous achievements that were made by the women and men of Somare’s generation, and if there remain many more mountains yet to be climbed for PNG, it is worth taking some time to remember the ranges which have been conquered already.

The second is that, like Caesar, Somare was and is a flawed human being. The truth or otherwise concerning the rectitude of his behaviour may show, as many suspect, an egregious capacity for corruption or impropriety. If this is the case, let his life be seen as an example, in all its irregularities, of the difficulties and temptations implicit in the type of power politics, PNG-style, and let future generations of political leaders learn from it how not to behave.

The final assessment is that over the five decades of his political presence in PNG, he has acquired a deeply-situated, almost visceral place in the national psyche. In May, Papua New Guinean radio and newspapers were reporting that anyone found repeating false rumours of Somare’s death would be subject to prosecution and punishment. Love him or detest him, Somare has become such an embedded part of Papua New Guineans’ lives that it is difficult for many to imagine what it will be like when he is gone. Rest assured, there will be a tremendous outbreak of national mourning when that day arrives, as it eventually will. His passing will be the final stage in Papua New Guinea’s maturing, from an adolescence marked by storms to what we all hope will be a prosperous and secure adulthood. It will be the occasion of much grief for times that have passed, but also of great promise for the future.

Share this story

Sir Michael Somare

Sir Michael Somare