The failed pursuit of pleasure

Alumni newsTucked away in a tiny office, in a large research centre, in the massive Melbourne Royal Children’s Hospital, is an academic dedicated to understanding emotional wellbeing.

He’s not a self-help guru or a chemist working for big pharmaceuticals, and neither is he a religious zealot. His work draws on major studies into social and emotional development over the last 35 years. His findings fly in the face of everything we have been told about how to lead our very best life. The key to leading a full and meaningful life, says Professor Craig Olsson, is let go of our obsession with happiness.

In 2014, Professor Olsson was appointed Director of Deakin’s Centre for Social and Early Emotional Development(SEED), a group of 60–plus researchers involved in projects covering topics including mental health and wellbeing, mental illness and disability, ranging from childhood through to adolescence, young adulthood and the next generation.

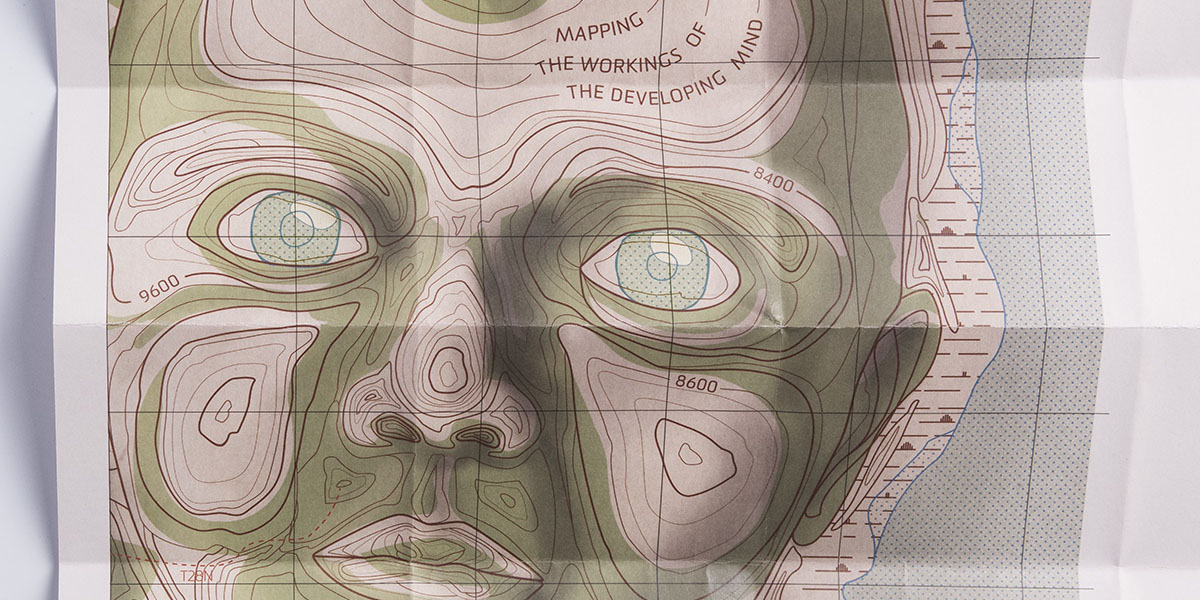

One of his key research projects is the development of a ground-breaking ‘atlas’, that maps out the key milestones in social and emotional development and requirements for people to live full and meaningful lives.

And not only are the results a departure from the traditional wisdom, the way the atlas is being developed is simply transformative, with some of the country’s most prestigious schools working with the Centre to turn their curriculum into one focused on supporting the atlas’ key recommendations.

'Once, the early explorers went out and charted a map of the world by drawing outlines of the countries,’ explains Professor Olsson. ‘Then da Vinci said, well if they can draw a map of the world, what about a map of the human body? So he started going down into graves and digging up bodies, and drawing them because this was his atlas. Well, we’re saying there is another atlas to be written, not of the human body, but of the development of the human emotional and social response.’

To build the atlas is a substantial project, one that starts with gathering evidence from a multitude of studies into every stage of development conducted in Australia and around the world over the last 30 years and beyond. The work of the project is also very much informed by original research conducted in some of Australia’s most mature studies of child development. Key among these is the Australian Temperament Project (ATP) Generation 3 Study, of which Professor Olsson is Scientific Director.

The ATP Generation 3 Study is one of Australia’s longest-running longitudinal studies of child development. Beginning in 1983, it has followed around 2000 young Australians over 35 years, from four months of age through to adulthood, and most recently, into parenthood with over 1000 offspring now recruited into study, first assessed in pregnancy then followed up at 8 weeks, 1 and 4 years after birth.

‘Long-term studies such as these are key to informing successful interventions,’ says Professor Olsson. ‘Unless you understand the foundations of emotional life, you can’t describe healthy development or know what’s going on when something goes awry, or know when and how you should intervene.’

According to Professor Olsson, addressing the factors that influence emotional regulation in early development, even before the age of one year, could have a profound impact on the number of mental health issues presenting in adults.

‘One of the things that our work is confirming here is the importance of secure based attachments between the infant and the mother and the infant and the father,’ he explains. ‘It’s all to do with the way the infant uses the mother or father to regulate their sense of security, their sense of being safe in the world.’

The quality of attachment has wide-ranging implications, not just in the social and emotional development of the individual, but how they go on to parent their own children.

‘Currently, we are looking at around 40 per cent of the population at the age of one having some form of attachment-based insecurity, which is a large percentage.’

Research into exactly why this figure is so high forms a central part of the atlas’ aim, which is to guide people in how to promote a secure start to emotional life and also defend against threats to it.

‘Our Centre addresses three core questions: what matters in development, if there’s a departure from those healthy structures how do we help bring the child back on track, and what’s translatable.’

‘These are the three organising questions,’ he explains. ‘We think there’s a lot of literature and evidence to support that attachment is something that matters. OK, so then we ask, what works? Well, globally there are a couple of interventions, one for example called Circle of Security.

‘Then you come to that question, what’s translatable? Well, Circle of Security is a time intensive specialist intervention, and therefore, expensive.’ So, the team investigates and develops ways to make a treatment more accessible and affordable, by delivering it, for example, through maternal health centres or schools.

‘We’re conducting research across all three of those questions.’

One of the potentially controversial findings of the researchers is that the best track to a full and meaningful life is to give up this quest for happiness.

‘The new cognitive paradigms now are very much trying to teach people that we are complex organisms with many ranging emotions in the course of one day, and that we should be learning how to relate, rather than to control them,’ explains Professor Olsson.

‘Somewhere along the way, as a culture, we got deluded. Even from the Industrial Revolution there was an increasing cultural belief in our ability to control things. And we rose on the hope of being able to control everything, even old age and death.

‘A full and meaningful life isn’t a life full of happiness,’ he continues. ‘It’s a life where the full spectrum of emotions can be encountered and processed in order to grow the individual. If we want the best for our children we need to teach them how to feel. We need to teach them how to be scared; how to be angry; how to be sad; and how to be happy.’ Rather than seeing negative emotions as things to get rid of, it is important that we shift gears and focus on accepting the many and varied emotions and feelings we experience daily.

According to Professor Olsson, growing a human who feels safe and secure experiencing all emotions – good or bad – starts within the first year of life. In a healthy attachment scenario, he says, a baby cries and the mother or father embraces the child and soothes it through the arc of heightened response, until they calm down again. The child learns many times during the space of a day that this is the normal dynamic of an emotion. ‘But the carer who can’t cope with negative emotion very well and who wants the child not to cry, could very easily stop the child midway through the cycle. The child starts to believe that there is an infinite expansion of this emotion, and learns to be afraid of it, or to avoid it.’

While information for new parents could be disseminated through maternal and baby health centres, Professor Olsson believes that it is in schools that the atlas of emotional development will make the most difference in the social and emotional growth of the next generation.

‘Ideally, the atlas would inform a curriculum that combined psychology and education – a curriculum that is really informed by science and had expectations of social and emotional development across the early life course from prep to Year 12.’

The Centre is already in discussions with some of Australia’s biggest private schools, but he says that interest from schools in the atlas is widespread and growing.

‘What will change the game is how we build the wave with education and psychology over the next 10 years,’ says Professor Olsson. ‘If we have powerful schools and educational lobbyists who see the value in the curriculum like this, education has the potential to be transformed in exciting and new ways.’

Share this story