Visit from 'father of atom probe tomography'

Research news

One of the world’s most highly regarded metallurgists - known as the “father of atom probe tomography” - Professor Michael Miller, has recently visited Deakin’s Institute for Frontier Materials as a Thinker in Residence.

Professor Miller played a key role in the development of the local electrode atom probe, which has helped to revolutionise metallurgy, to the benefit of numerous industries around the world.

After conceiving the idea for atom probe tomography in early 1983, he joined Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) in Tennessee - one of the world’s leading science and technology labs (largely funded by the US Department of Energy), where he created his first prototype in 1986. He remained at ORNL for the next 31 years before retiring in 2014.

Today, atom probe tomography offers unparalleled insight into the microstructure of materials, through atomic resolution chemical and spatial analysis in three dimensions. It has led to significant advances in technologies, ranging from semi-conductors, to jet engines, to nuclear reactors.

Its benefits have centred on understanding the role of each element in materials, which has led to the production of stronger, lighter and tougher metals that, in the case of jet engines, can operate in higher temperatures, with longer life and less pollution.

The IFM is home to one of only three Australian local electrode atom probes (LEAP 4000HR), which are based on Professor Miller’s research. Deakin made the purchase in 2013, through funding from the ARC Linkage Infrastructure, Equipment and Facilities scheme.

During his visit, Prof Miller provided training to students, post-doctoral researchers and staff on advanced microscopy techniques.

He also worked with long-time collaborator, Deakin’s Dr Ilana Timokhina, with whom he is undertaking a joint ARC Discovery project on improving advanced steels through the heat treatment process known as precipitate strengthening.

“We are optimistic that we can create steel with greater strength and ductility, for use in more adverse conditions, such as earthquakes, tornadoes and cyclones, or under water,” Professor Miller said.

He added that he was “very impressed” with the world class metals research being undertaken at Deakin, noting that the demands for stronger, lighter steel are growing, as buildings become taller and resources more precious.

As to how the probe works, Prof Miller explained that it can determine the identity of a single atom on a metal surface, achieving atomic magnification through a highly curved electric field and “time-of-flight” mass spectrometry (where the mass-to-charge state ratio is determined via a time measurement).

The resulting data set spans hundreds of nanometres in depth and contains the elemental identities of up to a billion atoms – with a level of detail hard to fathom, considering that metal looks flat to the naked eye.

“The probe enables scientists to reconstruct where all the atoms are in an object, with very close to atomic precision, for all the elements in the periodic table,” he said.

“Once we know this, we can start to predict properties and fine tune alloys to make better use of elements, in terms of cost effectiveness, through minimising quantities of the more expensive elements required and being more frugal with rare earth metals.”

Apart from his interest in science, Professor Miller is also an accomplished photographer, having published 20 books that feature his photographs from around the world, depicting wildlife in Africa and the polar regions, lighthouses on Victoria’s shipwreck coast, and showcasing numerous countries he has visited.

In fact, he attributes his interest in photography as a partial catalyst for his atom probe breakthrough.

“I spent many hours in the darkroom as a young man doing a lot of low light photography and that experience helped to build my understanding of photography,” he said.

“I was always interested in science, physics, chemistry and maths as a child. I was intending to pursue corrosion, but when I went to Oxford to discuss my PhD topic, I met a metallurgy professor who had just built one of the first atom probes for metallurgical purposes. The interview was scheduled for 20 minutes, but I came away two hours later - with a new direction. I got in at the right time, with the right people, to make a difference.”

Share this story

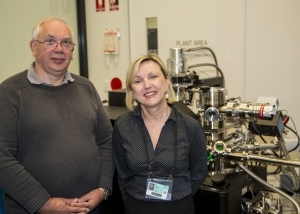

Thinker in Residence, Professor Michael Miller, with Deakin's Dr Ilana Timokhina.

Thinker in Residence, Professor Michael Miller, with Deakin's Dr Ilana Timokhina.