GFC has brought academics to the policy table, US expert

Research news

The Global Financial Crisis brought massive changes on world economies, but one positive outcome is that it has helped to bring academics to the decision-making table - leading to improved policies and strategies, such as quantitative easing, in a number of countries.

Deakin economics staff and students recently got to hear from one of the world’s leading economists, Professor Chris Waller, who is directly involved in helping to manage the world’s second-largest economy, as Senior Vice-President and Research Director of the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis - one of the 12 US Federal Reserve Banks that are responsible for US monetary policy.

Prof Waller paid a week-long visit to Deakin’s Centre for Economics and Financial Econometrics Research (CEFER), where he shared his experiences with staff and students.

Having taken leave from his position as Professor of Economics at the University of Notre Dame, to work for the Federal Reserve System, Professor Waller said that economists in academia now play a much stronger role in economic policy-making in the US.

“Many of the policy makers in the US Federal Open Market Committee now have PhDs in economics,” he said.

“When you think about deciding monetary policy in difficult times, academics are some of the smartest people to provide advice. To follow what’s going on, you have to be at that level of interaction. (For central banks) the best strategy is to have staff who can engage with academics or policy makers.”

“There are new policies and ways of doing things, and in some sense the academic literature is leading the way,” he added.

Professor Waller is undertaking a joint research project with CEFER’s Professor Pedro Gomis Porqueras, which is focussing on two research strands: assessing how monetary policy affects the way agents settle transactions in financial and goods markets; and the efficacy of quantitative easing (QE) conducted by the US Federal Reserve.

QE is the strategy of buying assets, usually government bonds, with newly printed money and - when interest rates are around zero - provides a particular mechanism of injecting money into the economy, as a means of encouraging financial institutions to lend more, and thus increase consumer and business spending. With a focus on minimising the risk of inflation, QE has been dubbed the "Goldilocks approach” - not too hot, but not too cold.

During his visit, Professor Waller gave a presentation on the impact of quantitative easing. His paper outlined the value of QE for stagnant economies, like the US and Europe, where short-term interest rates have hovered around zero since the Global Financial Crisis in 2007. Implemented in the US (since 2008) and Britain (since 2009), and the European Central Bank since January this year, quantitative easing seems to be working, Prof Waller argued.

“In the United States, we think that QE is having a beneficial impact on the US economy,” he said. “Short-term interest rates have been near zero for seven years, but there are lots of thoughts that rates could be raised in June or September this year.

“But we have done quite well, compared to Europe and Japan. Our unemployment rate is down from 10 per cent to 5.7 per cent, inflation is below the two per cent target and is looking like it’s going to come back - and the big collapse in oil prices is now rebounding so no deflation is expected.”

As far as Australia is concerned, Prof Waller believes, “there have to be trade-offs. It is a matter of when you want to take painful measures. It may be better to take some pain today, than in the long run.”

“We don’t see a lot of evidence that (all out) spending works,” he added. “It didn’t work for Japan or Greece. The Irish took the pain and now they are growing. They bailed out their entire banking system at an enormous cost, with reduced spending, and raised taxes. Now they have cleaned up and they are off.”

Share this story

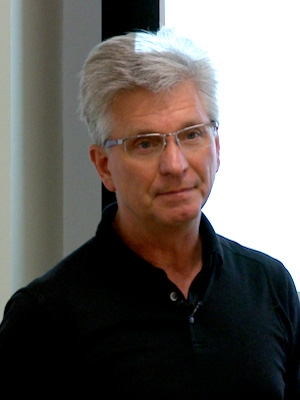

Professor Christopher Waller.

Professor Christopher Waller.